Gulcin Ozkan, King’s College London

The Turkish lira hit its weakest ever level against the US dollar on August 7, trading at 7.36 at one point, having lost nearly 20% of its value since the beginning of the year. It comes almost two years to the day since Turkey was last hit by a massive currency crisis, following the economic sanctions imposed by the US government after Turkey detained American pastor Andrew Brunson on terrorism charges.

On that occasion, the lira stabilised after Turkey’s central bank raised interest rates by 625 basis points (6.25%). This brought a relative calm, but only temporarily. The lira has been on life support for the past two years and the economy has continually struggled.

US dollar vs Turkish lira

The lira’s latest tumble is even more dramatic than it appears because the US dollar has itself been losing value. The dollar is down 9% against a basket of other currencies due to investors deeply unimpressed by America’s handling of the COVID-19 crisis. So why is the lira in so much trouble?

Emerging economies and COVID-19

COVID-19 is not the whole story, but it is a good place to start. It is now widely acknowledged that the coronavirus has posed an even greater challenge to emerging economies like Turkey than the 2007-09 global financial crisis.

Whereas the global financial crisis affected emerging economies only indirectly, mostly sparing those who were less exposed to it, COVID-19 is a different story. Nations are having to cover the cost of a public-health crisis while coping with the wider economic fallout both at home and further afield.

As most advanced economies ground to a halt in lockdown, their demand for exports from emerging markets tanked. A good example is international tourism, which is forecast by the OECD to be down 60% this year. This has dramatic financial consequences for the likes of Indonesia, Thailand, and of course Turkey.

These countries can’t afford huge rescue packages like the UK, US and EU, so their economies are significantly more vulnerable. They have also been hit by massive capital flight. In just four weeks at the beginning of the crisis, a third of the investments into emerging nations’ bonds over the past four years were sold. This was four times the capital outflows of the 2007-09 financial crisis. It has spelt disaster for these countries, who rely on this capital for financing domestic investment and hence economic growth.

Especially for countries like Turkey that persistently run current account deficits, meaning they import more than they export, this drying up of external finance is a strong harbinger of a balance-of-payments crisis. This is where investor confidence falls so much that the local currency collapses and the country can’t cover its debts or pay for essential imports. Various emerging economies risk such a crisis if current conditions prevail for an extended period, and Turkey is clearly one of them.

Turkey’s vulnerabilities

Turkey has been considered among the riskiest emerging markets in recent years, categorised as one of the “fragile five” along with India, Brazil, South Africa and Indonesia. Turkey earned its place for running large current-account deficits, and although there have been improvements on and off, it has continually relied on external financing as its engine of growth.

Turkey has long survived by attracting strong capital inflows, prompting strong credit expansion which in turn encourages economic growth. But this virtuous cycle turns vicious in bad times, dragging the lira to the brink.

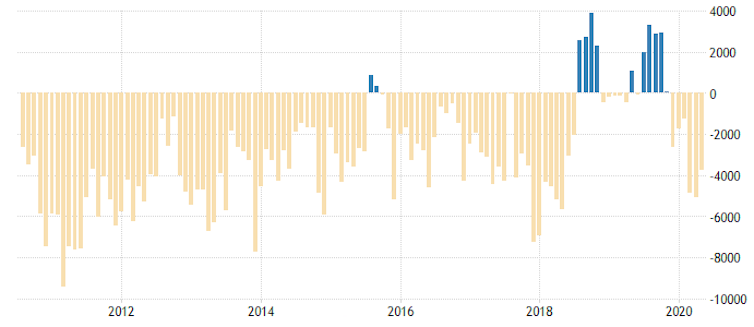

Turkey’s current account, US$ millions

Then there is politics. Since 2014, Turkey has had at least one election every year except 2016. There were local elections in 2014, two general elections in 2015, a referendum on the government system in 2017, general and parliamentary elections in 2018, and local elections in 2019. This has put almost continuous pressure on the authorities to spend money and keep stimulating the economy with interest rates low enough to encourage more borrowing.

What now

There are three well-known measures that one can deploy against a falling currency. Raise interest rates, buy the currency using national foreign-exchange reserves, or adopt capital controls to prevent foreign currency outflows.

Capital controls may stabilise investment flows in the medium term, but there is no compelling evidence that they work in the heat of a currency crisis. So Turkey’s options are to raise interest rates and/or use foreign exchange reserves. The bad news is that the central bank has been defending the lira for several years using foreign-exchange reserves already. Reserves are almost depleted, which is why the currency has been taking such a hammering lately.

Turkey could either obtain more foreign currency by borrowing from international institutions like the IMF, or raise interest rates like it did in 2018 (the base rate is currently 8.25%). But both options are political minefields right now.

President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has a well-known conviction – contrary to conventional economic theory – that high interest rates cause high inflation. And his party, the ruling AKP, has long told the people that Turkey is no longer a country that needs IMF assistance.

Turkey’s leaders have made it common knowledge that neither option will be sought unless everything else fails. When the lira was last under acute pressure in May, the authorities signed a currency swap agreement with Qatar for US$15 billion (£11.4 billion).

This time, they have been trying everything from forcing Turkish banks to borrow at the higher-cost overnight facility (an interest-rate rise by another name) to reducing domestic lending, since this weakens the lira by boosting demand for US dollars. Such measures may buy time, but are unlikely to prevent further melting of the lira unless the government moves on the two main fronts.

Even then, these won’t solve Turkey’s long-running problems. The current model based on external finance, cheap credit and booms in consumption has run its course. The real question is what will replace it.

Gulcin Ozkan, Professor of Finance, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.